New Hope Rural Leprosy Trust

Probably the best way of introducing the work of New Hope is to recount some of the early experiences of the founder of the Trust, Eliazar Rose, in the introduction to his book “The Ring of Capital L”:

I was in a leprosy colony taking skin biopsies when one day a woman came in and sat on the broken step of the small temple which a local businessman had built. He had in fact encroached on a piece of Government land allocated to the colony.

I was in a leprosy colony taking skin biopsies when one day a woman came in and sat on the broken step of the small temple which a local businessman had built. He had in fact encroached on a piece of Government land allocated to the colony.

The land was barren and stony – wasteland except for one corner of approximately one acre. That piece was almost prime rice land as it had a small spring fed irrigation canal at one point. The businessman owned the adjoining land and simply encroached on the piece that would at least have given the patients a few bags of rice. The temple was an appeasement to the colony to get them to back off with their constant appeal to the local government land revenue officer. The temple of course was built with sun baked mud bricks bonded with a mortar with very little cement. The building, not surprisingly, started crumbling with the first monsoon rains.

Jokingly I told her not to sit on the cracked step as the wall behind her might collapse and fall on her. She asked if that happened would she be killed?

I didn’t answer.

Her story was simple. She had leprosy for many years, taken treatment and stayed in her home because her husband was the village leader. He believed it was his responsibility to care for her against the social norms of the time.

He died and the village turned her out with the threat that, if she didn’t go, they would burn her house down.

She left alone and her married family stayed behind in the village.

In the same colony a year later a woman came in while we were distributing rations. It was mid summer and simply too hot for the old people to go begging. This was long before we started a programme of custodial care by having people sponsor the aged.

At the end of the long queue an argument started. I stopped helping the two paramedics weighing out rice to see what had happened.

The argument was about this woman who had been in the colony for a couple of weeks and was not on our register. The elders of the colony had said that she couldn’t get a ration because they feared that one extra would mean a fraction less for them.

Life in a leprosy colony is tough – Life in India for the poor is tough.

She argued that she had a piece of paper like them. Everyone had been issued with a ration medical card. She did have a piece of paper. It was a hand-written notice certifying that her husband had divorced her because she had contracted leprosy.

In the same year I watched from a small first aid post we had constructed in a colony as a bullock cart wandered slowly down the dusty track in the middle of the afternoon. The wind was hot and it had been a long day dressing ulcers. I wasn’t really in a good mood.

The cart creaked to a halt and a woman slipped off the back and squatted on the ground. Three men climbed down and came over. They announced they had decided to send her away as she had leprosy. They of course said they were doing a kind deed bringing her to a colony instead of simply sending her away with nothing.

One man was her husband, another was her eldest son and the third was from the lowest caste in the village. It had been his job to help her climb onto the cart.

They nodded when I asked if the ‘well conditioned bullocks and cart were theirs. They smiled with pride.

Something cracked inside me. I had the colony men drive the three of them out of the colony without their bullocks and cart.

They went to the local police station and tried to register a case. A lone constable came to the colony, or should I say as near as he dared; to the path leading to the colony. I told him that indeed the colony did have a cart and two good bullocks and that two men had come into the colony and tried to steal them. Did he want to come into the colony and verify it all?

The police inspector saw me in town that night and stopped me. We made a deal that the cart and bullocks should be sold within three days and that I should report that there were certainly no bullocks or cart in the colony.

The proceeds built the outcast woman a small mud-walled hut with a grass roof. Majji lived there in the colony for almost twelve years. She died in 1996.

I don’t know how often she smiled, but whenever I visited the colony she would nod and smile as I passed her hut.

It was during this time that I was employed to visit 13 leprosy colonies to see more than 2,500 patients on a monthly basis. Things seemed to happen when I was in the colony. I know these experiences have influenced the policy of our Trust to adopt an ‘open door’ approach.

One cold winter’s morning I cycled from the town where I stayed to five surrounding leprosy colonies.

The turn into one colony was at a junction on the highway. There was a tea shop on the corner where I went each month. The owner asked me where it was that I went when I visited. I told him ‘To the leprosy colony down the road’. He did not smile.

After that, whenever I stopped he would take a cup down from the top shelf and wash it out with hot water before pouring my tea. When I had finished he would pour hot water over the cup and place it back on the top of the cupboard.

The fear associated with leprosy is not something that is described in words, but rather by the actions, of others.

One month later I arrived at Jigabur leprosy colony. I was late because the monsoon rains had caused a river to flood. Thirteen houses in a small colony on the bank had been washed away when an embankment upstream had broken.

We got no sympathy from the local government flood relief officer. He considered it a blessing that the houses and people had been washed away in the night as it meant they were no longer ‘polluting the river’.

I didn’t know what to say when a new patient appeared before me for an ulcer dressing. I asked her name. She began to cry. She had been warned by her family never to mention her name even when they forced her to leave their home and village.

She showed me a two rupee note her husband had given to her. He gave it to her with the advice that the best thing she could do with the money was to buy rat poison for herself.

I am not very fond of speaking at service clubs in India. I have the feeling they are out of touch with the social fabric of our society. A few times I have not been able to come up with excuses quickly enough and have felt obliged to attend.

At one such meeting (it certainly wasn’t at a Rotary Club), a member asked if I could please visit his home the next day. I knew by the way he spoke there was ‘leprosy in the house’.

His brother’s wife was in what I will simply describe as border line leprosy trauma. She was pregnant with her third child. The husband was a lawyer and the brother, incredibly as it seems, was a doctor.

Money was not the problem. Their request was simple – could I find a place in one of ‘those places’ where ‘they’ lived and build her a ‘nice place’. The end of this story is too sad for me to write about, even after 15 years.

It is my belief that if we can change the attitude of people in India towards this now curable disease, we can make other social changes.

If we can change the attitude to a disease whose name strikes terror just by its utterance, then getting other social changes will be easy. This policy, this belief, is happening in areas where we work.

Nowadays we see fewer and fewer people being turned away from their families, their homes and their villages because of the stigma associated with leprosy.

Some people allege that young people become leprosy paramedics simply because they can’t get a job elsewhere, or because it pays reasonably well (at least today it does).

I disagree, because you need to have a heart in the right place, you have to have a depth of compassion and courage, to write LEPROSY PARAMEDICAL on papers, that goes far beyond the negative comments that some people still make.

Although New Hope was established originally to help those suffering from leprosy, its work has expanded to include tribal people in general, street children and victims of ‘natural’ disasters.

Since its foundation New Hope has carried out health inspections on over one million people in western Orissa. Over 6,000 people have been identified with leprosy and most have received treatment. Over 5,000 have been cured.

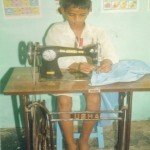

In addition to the hospital, the only one of its kind in western Orissa, the Centre accommodates:-

· a hostel for children with physical and mental disabilities (mainly polio) –

· calliper and shoe making units

· administrative block, and staff and patient accommodation

· accommodation for visitors, surgeons and students

· a weaving unit

· a shop for the use of patients

· laboratory

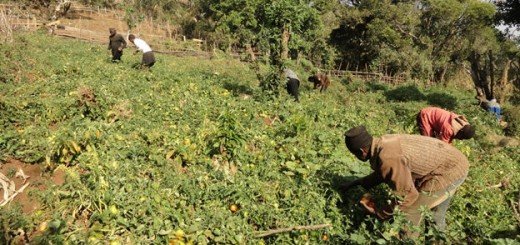

· vegetable gardens for patients

· occupational therapy unit

· savings and credit facility

New Hope also has homes for old people, disabled children and for street children.

Leprosy Colonies

In the leprosy colonies it serves, New Hope treats 2,500 patients on a monthly basis and has extended its work to the 76 villages of a remote hilly and forested tribal area named Raghubari.

In all its areas of operation New Hope provides anti-tetanus and polio immunisation, iron and folic acid supplements and safe delivery kits for pregnant women.

Street children

Street children are a manifestation of societal malfunctioning and an economic and social order that does not take timely preventive action. Today, street children command a great deal of attention because of their sheer numbers and high visibility. Street children are found in large numbers in all Indian cities. They are forced onto the streets because they cannot cope with their family situation. A street child is forced to be an adult at an early age. He/she has to struggle for survival and earn an income for day-to-day living. By running away from their families, these children are making a major decision and even displaying their anger towards their irresponsible parents.

The need for systematically observing and deeply understanding the behaviour of street children must be emphasized. These children are not substandard ignorant kids. They have acquired the valuable knowledge, attitudes, emotions, abilities and skills that are necessary for their survival on the street. Though self-esteem is the answer to all childhood problems, street children have a weakly developed identity. This identity is derived from their interactions with their peers on the street and with adults who often abuse or deceive them, instilling in them fear or rejection.

Although each child has a different story to tell, most of them have irresponsible parents and experience poverty and marginalisation. Parents are models, whether they want it or not. It is in the give and take of the parent-child and other relationships that the child finds a sense of security and self-esteem and the ability to deal with complex inner problems. But in the context of street children, the parents’ behaviour is often so cruel that the child makes a heroic decision to walk out on them into urban uncertainty. Poverty often overwhelms and infuriates the child rummaging through a garbage bin for discarded food. Ironically, food becomes an escape for street children. Their ravenous appetite and the fear of hunger compel them to eat every scrap they can get their hands on. Thus the street children have a combination of different characteristics. In varying proportions they can be emotionally vulnerable, physically resilient, naïve, wary and street-smart.

In spite of the increasing visibility of India’s ‘overall’ development on the international scene, the ‘inner contribution’ has been that the enrichment of a few is accompanied by the marginalisation or exclusion of millions of others. The real issue is that development continues to benefit some people, while many others are left out and pushed out. The phenomenon of street children has its roots not just in what meets the eye (poverty, family problems, etc.) but also in this whole gamut of development itself.

Child labour

Working children are everywhere but invisible, toiling as domestic servants in homes, labouring behind the walls of workshops or hotels or on hidden from view plantations. Millions of children who work as domestic servants and in unpaid household help are especially vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Millions of others work under horrible circumstances. Child labour is a pervasive problem throughout the world, especially in developing countries. It is prevalent in rural areas where the capacity to enforce minimum age requirements for schooling and work is lacking. Children work for a variety of reasons, the most important being poverty and the induced pressure upon them to escape from this plight. Though children are not well paid, they still serve as major contributors to family income. Working children are the objects of extreme exploitation in terms of toiling for long hours for minimal pay. Their work conditions are especially severe, often not providing the stimulation for proper physical and mental development. Many of these children endure lives of pure deprivation.

Despite restrictions on child labour, children do work. This vulnerable state leaves them prone to exploitation. The International Labour Office reports that children work the longest hours and are the worst paid of all labourers. They endure work conditions which include health hazards and abuse. Employers take advantage of the docility of the children, recognizing that these small ones cannot legally form unions to change their condition. Such manipulation stifles their development. Deprived of the simple joys of childhood, these children are relegated to a life of drudgery.

However, abolishing child labour has its own limitations. First, there is no international agreement defining child labour. Countries not only have different minimum age work restrictions, but also have varying regulations based on the type of labour. This makes the limits of child labour ambiguous. Most would agree that a six-year-old is too young to work, but whether the same can be said about a twelve-year-old is debatable. Until there is global agreement which can isolate cases of child labour, it will be very hard to abolish.

Child labour is a significant problem in India. The major determinate of child labour is poverty. Even though children are paid less than adults, whatever income they earn is of benefit to poor families. Some parents are of the opinion that formal education is not beneficial and hence children learn work skills through labour at a young age. Another determinate is access to education in some areas. Education is not affordable, or is found to be inadequate. With no other alternative, children spend their time working.

Child labour can’t be eliminated by focusing on one determinant, be it education or brute enforcement of child labour laws. National and state Government must ensure that the needs of the poor are fulfilled before attacking child labour. If poverty is addressed, the need for child labour will automatically diminish. Children are growing up illiterate because they have been working and not attending school. A cycle of poverty is formed and the need for child labour is reborn after every generation.

If you would like to support the work of the New Hope Rural Leprosy Trust this can be done through its sister organisation in the UK: The New Hope Rural Community Trust.